Co-authored by Duke Bass Connections team: Braydon Madson1, Gabrielle Moreau2,3, Kiera O'Donnell4, Henry Park2, Wenrui Qu1, and Nathan Yang2

1Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, 2Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, 3University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, 4Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham NC 27708

Edited by Steve Anderson

Saltwater intrusion and Sea Level Rise is a known threat along the coastline – but what can be done about it?

Coastlines are subjected to rising sea levels, sinking land, more severe coastal storms, and more intense droughts under current climate conditions. These changes lead to inputs of marine salts into freshwater-dependent coastal systems impacting social and ecological communities that rely on freshwater.[1] The penetration of salinity into the coastal interior is exacerbated by groundwater extraction and the high density of canals and ditches throughout much of the landscape. Together saltwater intrusion and sea level rise (or SWISLR) creates significant changes and challenges for the social-ecological systems within the coastal plain (figure 1). SWISLR causes ecosystem changes, such as the erosion of coastal landscapes or changes in ecosystem biological composition, and causes challenges for the social system, such as a reduction in crop/fish yields or degradation of coastal infrastructure. Studies on the impacts of SWISLR are growing in number as the issue is becoming more apparent. News articles about the increasing ghost forests along the coastlines,[2,3] and about threats to clean water supply[4,5] throughout the globe have brought public attention to the slow persistent hazard of SWISLR. Specifically for the coast of North Carolina there are expansive swaths of ghost forests, agricultural losses, drinking water becoming compromised, and higher flood occurrences. Coastal North Carolina is one of the hotspots of SWISLR exposure in the United States and residents are worried about the risk that comes with living on the edge.[6] However, researchers are still working to understand the full socio-ecological impact of SWISLR.

To combat this complex problem, a research coordination network (RCN) has been created focused on understanding SWISLR as a whole[7]. The primary focus of the SWISLR network is to build a connective intellectual network where new research and ideas can be supported and disseminated easily. The SWISLR network has developed and refined a set of key interdisciplinary questions that address the knowledge gaps present in SWISLR research: 1) Who is engaged in decisions about climate and SWISLR adaptation and mitigation? 2) What proportion is currently vulnerable to ecosystem transition as a result of SWISLR? 3) How are water management and climate change interacting to determine the magnitude of SWISLR? 4) What are the consequences of SWISLR for farms and coastal fisheries? 5) How is SWISLR affecting the structure and biodiversity of ecosystems? And 6) How are coastal communities responding to and managing SWISLR? In identifying these knowledge gaps, the SWISLR network has highlighted areas of future work and a call to action.

Figure 1. The general movement of saltwater intrusion and sea level rise along a coastal landscape with both natural and managed landscapes potentially occurring. The movement of saltwater into interior systems is shown by the light blue arrows. Impacts and extent of intrusion depend on the type of land use being affected (e.g., agriculture and timberlands) and the natural and human features of the surrounding landscape. Note: this figure was created by the SWISLR RCN and Hiram Henriquez of H2Hgraphics.

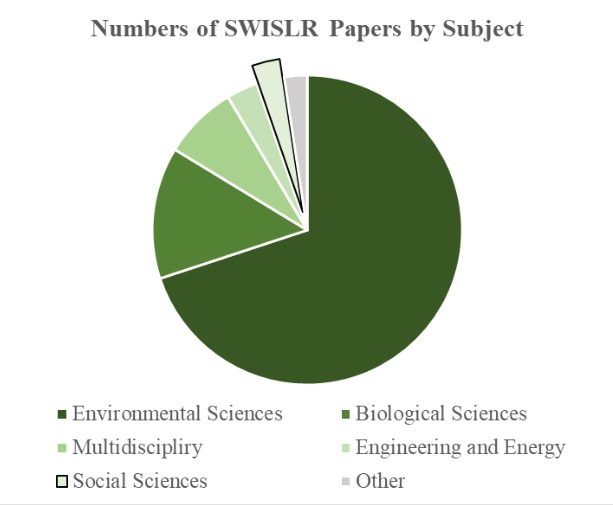

While a lot of work has been done to quantify the extent of SWISLR, fewer studies have considered the effects of SWISLR on coastal communities. To understand the current state of SWISLR social science and to begin answering questions 1 and 6 for the SWISLR network a team of interdisciplinary researchers at Duke University are conducting a meta-analysis of social science work related to SWISLR. Papers were collected to get a broad sense of how SWISLR was represented in the research. Papers were found on the web of science and Scopus journal databases using the key words of “saltwater intrusion” or “sea level rise”. This search resulted in about 3,056 research articles covering the topics of SWI or SLR (figure 2). The papers within the subject area of social science were downloaded for screening to better understand what perspectives are, or are not, being told in the literature and to get a sense of what is being done globally about the SWISLR threat. The resulting 520 studies were further filtered down to 104 by excluding studies that did not look at SWISLR or did not contain a community survey element. The work of extracting the 104 studies is currently ongoing, but some major themes have already arisen. The researchers have found that the papers, although few, include a wide range of individuals and locations. The myriad perspectives resulted in a wide array of SWISLR mitigation outcomes.

Figure 2. Proportion of subjects from the initial search of 3,056 SWISLR focused papers. The subjects analyzed further for SWISLR social science papers are in orange.

What information about SWISLR is missing and what perspectives are not being told?

The researchers for this project are interested in who is studying SWISLR, where SWISLR studies are taking place, how SWISLR is impacting the populations of these areas, and what the means of response to SWISLR impacts currently are. With these four focuses, the goal is to not only better understand the current state of SWISLR research, but to have a better understanding of the influence of SWISLR research as well. The current literature extracted revealed three major places that SWISLR research is being completed: The US Gulf and east coast, The Mekong Delta in Vietnam, and in river basins throughout Bangladesh. The studies reviewed so far provide perspectives from a wide range of individuals, from victims of natural phenomena to farmers impacted by SWISLR and include the perspectives of local officials who are often responsible for responding to SWISLR impacts. Continuing this review will help to highlight communities currently under threat of SWISLR impacts and potentially identify who is being excluded from the proverbial climate risk prevention table. In understanding who is studying SWISLR and where the studies are taking place, we hope to capture whose viewpoints are reflected in the literature, and whose are missing.

The expected trend through the literature is that coastal residents, especially those disadvantaged rural populations and communities, suffer the highest impacts from SWISLR. This trend is present for many environmental hazards, and although most research on social vulnerabilities to coastal hazards focus on acute events such as hurricanes or typhoons, there is a growing body of literature on sea level rise and saltwater intrusion finding this same trend. SWISLR leads to disparities in the ways in which different genders, races, and social groups deal with impacts on agriculture, aquaculture, freshwater, land use and other aspects. For example, female farmers are forced to pursue in-place farming adaptation strategies with limited external resources while relying on informal social networks for weather and climate information (Ahmed & Kiester, 2021). Additionally, current and future predicted flood risk are projected to unevenly impact poor and primarily Black communities in the United States (Wing et al. 2022). In a recent Reuters Hot List of highly influential climate scientists, only 5 were African and less than 15% were female.[8] It is important to understand whose perspectives current SWISLR research reflects so that we can understand whose voices are missing from our current understanding of SWISLR risk and prevention.

What is being done about SWISLR risk?

One of the questions asked within the review is “what are the mitigation or adaptation techniques taking place or being suggested within the literature?” Many studies include the process of suggesting techniques or topics for future studies, but quite a few of the studies documented adaptation that farmers, residents, and planners can/should take to protect against SWISLR. Many found that education and the sharing of knowledge increases the resilience of a community. Others advocated for economic and social support through federal or state agencies. Beyerl et al. 2018 summarized how residents of three Pacific small island states relate the government and non-government organizations to funding and education on climate change adaptation practices. Another example is the survey completed by Carpenter 2020 of residents throughout the US East Coast which found state and federal agencies ranked highly as funding sources for sea level rise adaptation planning. This study still highlighted how funding sources should be decided using public meetings. Still more focused on concrete options such as crop rotation, rain gardens, employing adaptive farming and fishing techniques, or implementing more monitoring stations in key local risk locations. One adaptation technique mentioned in many papers, outside of the United States, and within varying demographic groups was migration. There was a wide range of uses and success regarding migration as an adaptation technique. For example, in Vietnam, heads of households (usually the father) would migrate to a major city during times of environmental disaster to earn money through other means. This money would be sent back to support the family, so the rest of them would not need to move (Tran et al. 2023). However, during this woman have more family responsibilities and face additional stress when men migrate because of their heightened climate vulnerability and challenges of operating in a patriarchal society. So far, it is unclear whether migration is a commonly used adaptation technique. What is clear is the common plea to increase community participation and collaboration when making climate decisions. Through this review methods like the Talanoa method (Bennett et al. 2020) and participatory GIS (Morse et al. 2020) have been identified that successfully include local community perspectives. As the researchers continue to review SWISLR papers they plan to highlight more perspectives and identify the gaps in our understanding.

Learn more!

[1,7] Saltwater Intrusion and Sea-Level Rise Research Coordination Network (SWISLR RCN) [2] 'Ghost Forests' Threaten New Jersey's Water, Ecosystems [3] The Swift March of Climate Change in North Carolina's 'Ghost Forests' [4] Here's a Look at the Water Crises That Might Be Coming to You Soon [5] New Orlean's Saltwater Scare Is a Reminder of a Nationally Looming Threat [6] Down East Deserves the County's Support

Recent Publication: Saltwater Intrusion and Sea Level Rise Threatens U.S. Rural Coastal Landscapes and Communities

Literature Cited

Ahmed, S., & Kiester, E. 2021. Do gender differences lead to unequal access to climate adaptation strategies in an agrarian context? perceptions from coastal Bangladesh. Local Environment, 26(5), 650–665.

Bennett, K., A. Neef, and R. Varea. 2020. Embodying Resilience: Narrating Gendered Experiences of Disasters in Fiji. Pages 87–112 in N. Andreas and P. Natasha, editors. Climate-Induced Disasters in the Asia-Pacific Region: Response, Recovery, Adaptation. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Morse, W. C., C. Cox, and C. J. Anderson. 2020. Using Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS) to Identify Valued Landscapes Vulnerable to Sea Level Rise. Sustainability: Science Practice and Policy 12:6711.

Tran, D. D., T. D. Nguyen, E. Park, T. D. Nguyen, Pham Thi Anh Ngoc, T. T. Vo, and A. H. Nguyen. 2023. Rural out-migration and the livelihood vulnerability under the intensifying drought and salinity intrusion impacts in the Mekong Delta. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 93:103762.

Wing, O. E. J., W. Lehman, P. D. Bates, C. C. Sampson, N. Quinn, A. M. Smith, J. C. Neal, J. R. Porter, and C. Kousky. 2022. Inequitable patterns of US flood risk in the Anthropocene. nature climate change.

Cover photo by Kiera O'Donnell, Down East U.S. Post Office in Marshallberg, NC