Author: Katie Whittington

Submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) is the often-unsung hero of a host of environmental benefits including water quality maintenance, carbon storage, and sedimentation management in estuaries. Wild celery is a type of SAV, or underwater grass, at the center of an environmental education project called Growing Wild Celery to SAVe Our Wetlands: A Grassroot Collaborative. Located at Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge in the Virginia portion of the Albemarle-Pamlico region, this project combines classroom education with immersive hands-on learning in hopes to revitalize wild celery growth throughout the estuary and wetlands in Back Bay. Project leader Jody Ullmann has collaborated with a number of community partners to bring this project to life.

Project Foundations

Growing Wild Celery to SAVe Our Wetlands: A Grassroot Collaborative was born out of a need to restore SAV growth to the Back Bay region and an interest in environmental education from project leaders. Led by the Atlantic Wildfowl Heritage Museum (AWHM), this project aims to engage dozens of students in hands-on learning about wild celery and SAV-dependent ecosystems. Combining in-class lessons and wild celery growth with a field trip to Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge (BBNWR) for plantings, the collaborative project will restore Back Bay’s SAV-dependent waters with wild celery and inspire future generations of environmental stewards in the process.

The project was funded with support from an APNEP Engagement and Stewardship Grant, which provided the AWHM with a total of $30,000 for project implementation. Leveraging funds and resources from both NC and VA, the project involves students and teachers throughout southeast Virginia. The project is under the leadership of the AFHM, with museum staff serving as leadership support for Project Lead and Educational Consultant Jody Ullmann. According to Ullmann, this project was fa goal of hers for years, dating back to when she first met research scientist Dr. Sara Sweeten in 2022 at the North Landing River and Albemarle Sound Symposium hosted by the City of Virginia Beach. Here, they bonded over their mutual interest in creating a program for students to grow plants in the classroom. “When this [APNEP] grant came forward, the first person who came into my mind was Dr. Sweeten,” Ullmann says. After giving her a call, they were both all-in. “It worked out really well,” she continued. “I think it’s such a perfect fit with the Atlantic Wildfowl Heritage Museum’s goals and the goals that were in the grant” including SAV restoration, water quality maintenance, and habitat protection. “It was a nugget in the back of my head two years ago and now we’re doing this thing together to make it happen,” Ullmann says of Dr. Sweeten.

Dr. Sweeten is a research scientist with her company SAVY Aquatic Restoration. She obtained her PhD in Fish and Wildlife Conservation in 2015 at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (otherwise known as Virgina Tech) where she “accidentally” got involved with SAV in 2018. When a group of students left Vallisneria americana , AKA wild celery, in her building on Virgina Tech’s campus, she started messing around with it for fun before eventually making it the center of her research for much of her career. She now regularly plants and studies wild celery in the Back Bay area and assists project leaders during teacher workshops, classroom lessons, and student field trips. This is part of the reason why Ullmann decided to base this project in Back Bay; Dr. Sweeten has already conducted test plots of wild celery in the area proving that growth would be successful.

The Growing Wild Celery project also helps further implementation of APNEP’s 2020 Memorandum of Understanding between six environmental and natural resource agencies in Virginia and North Carolina. The MOU outlines a commitment between both states to collaborate on addressing environmental issues and protecting the watersheds in the shared river basins that flow into Albemarle Sound. Although much of the APNEP region falls within North Carolina, a crucial part extends to Virginia including Back Bay located in the Pasquotank River Basin, as it’s known in North Carolina, or Southern Rivers Watershed in Virginia. Projects like these are important to raise awareness about the connections that Virginia residents have to the Albemarle-Pamlico region and foster environmental stewardship. Surveys conducted by Ullman and other project partners have shown that many Virginian teachers do not realize their watersheds drain to the Albemarle Sound and not the Chesapeake Bay. Through previous collaboration between the project partners, resources and toolboxes have been developed for use by educators in the region. Novel projects like this one are continuing to help further this goal of effective interstate collaboration and education between APNEP and its partners.

The Importance of SAV

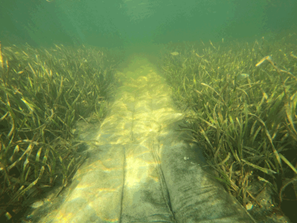

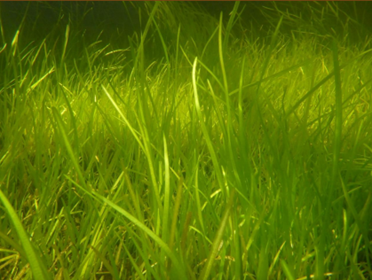

SAV, or underwater grasses, are little known, important estuarine habitats that APNEP has focused on protecting for years through its SAV partnership and monitoring network. SAV is crucial to the function of estuarine ecosystems, as it creates valuable habitats for thousands of fish and as many as 50 million small invertebrates and serves as important feeding grounds for waterfowl and other species. It is also a protector of water quality, as it absorbs excess nutrients from the estuary and generates oxygen. Additionally, SAV decreases wave energy, assisting in shoreline erosion prevention and boosting water clarity.

SAV is one of the most valuable habitats on the planet, and the Albemarle-Pamlico region is ranked third in the country for SAV abundance with over 136,000 acres of SAV calling the region home. This makes preserving it an issue of regional importance. SAV can live in both fresh and saltwater environments, with saltwater species more commonly known as seagrass. Wild celery is an underwater grass found in oligohaline, or less salty waters. The Albemarle Pamlico region is home to several species of low-salinity and high-salinity grass. The Back Bay and Currituck Sound region is well known for being a destination for sportsmen and hunting grounds for wintering waterfowl such as ducks and Canada geese, which rely on SAV for food.

Unfortunately, SAV is experiencing what experts like Dr. Sweeten are calling “underwater deforestation.” Although SAV is often hidden underwater, the benefits it brings to aquatic ecosystems are essential to their function. However, in recent years, excess sediment has created an “aquatic dust bowl” climate in many aquatic ecosystems, stunting the growth of wild celery and giving way to “underwater deserts.” Like trees on dry land, SAV acts like ground cover prairie plants for substrate (underlying substances or layers in water). They offer many of the same services and landscape as trees but below sea level.

Wild celery is ideal because “everything likes to eat them,” Dr. Sweeten says; and they are the foundation of a strong ecosystem. She adds that there is also a drawback, however, because they require extra protection and supervision in the early stages of growth. Her unique approach to cultivating wild celery involves growing it in freshwater aquaculture centers and then transplanting into habitats like Back Bay. As part of this technique, she installs fences around the plants to protect them from predation, something students and project partners do as part of this project. “[Dr. Sweeten] grows it [wild celery] to a point where...it can get light, and it’s not as affected by sedimentation,” Ullmann says . “We’re adding on to her previous work.”

|

|

|

|

Restoring SAV, specifically wild celery in historically SAV-rich ecosystems like Back Bay is important for improving water quality and clarity, reducing the severity and extent of flooding, and managing sedimentation. This project focuses on restoring wild celery, a type of SAV that thrives in low-salinity freshwaters, but there are many other types of SAV, like seagrass, t hat grow in saltwater. Projects that focus on restoring a specific type of SAV, like the SAVe Our Wetlands Collaborative, are the most fitting for long-term SAV restoration.

SAVvy Teacher Trainings

When the project came up, Ullmann said she wanted to involve many local teachers she knew who love to “do things outside the box and really get kids’ hands on stuff.” Beginning with a trip to BBNR and False Cape State Park (FCSP), the project invited 12 teachers from Virginia Beach and Chesapeake to an immersive experience where they discovered the history of Back Bay and importance of SAV while learning environmental education techniques. APNEP’s intern Katie Whittington joined the teachers’ first exposure to SAV in the field, as they got to see firsthand how it provides a valuable habitat for a myriad of estuarine organisms.

The educators gained valuable knowledge and hands-on experience while exploring BBNWR’s and FCSP’s mesmerizing natural areas and seeing SAV in its natural habitat. Activities included seining in Back Bay waters, electroshock fishing with Chad Boyce, a fisheries biologist with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, duck decoy painting, and kayaking with the FCSP staff. Erica Ryder, Visitor Services Specialist at BBNWR, and Rachel Harrington, Chief Ranger of Visitor Experience at FCSP, also led hikes through the refuge and state park highlighting the ecological wonders and rich history of the area.

Teachers also heard presentations from park rangers, Dr. Sweeten, and Whittington about their work with Back Bay/False Cape, wild celery research, and APNEP, respectively. On this educational, collaborative, and immersive two-day trip, teachers and project leaders alike remarked how enjoyable and enlightening the training was, with many educators expressing interest in participating in the classroom portion of the project as well.

Ullmann said that False Cape has been an amazing partner, highlighting the symbiotic relationship they share. The project’s teachers get a valuable experience learning about SAV in its natural habitat and False Cape gets to educate them about their programs. According to Ullmann, many teachers come back with their students for field trips to both areas after trainings like these.

SAV Education In and Out of the Classroom

After the workshop, the teachers will return to their schools in the fall ready to teach their students about the Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds, as well as SAV and its importance in aquatic and estuarine systems. The schools that are chosen to grow wild celery in the classroom will be visited by Ullmann and Sweeten to determine the best equipment and set up needed to grow the plants. Come October, they will virtually meet with each class to explain and excite them about the project and teach lessons about SAV and the ecology of the Back Bay area. After winter break, students will use this knowledge to begin growing and caring for plants at their own schools.

The students will be emulating Dr. Sweeten’s techniques as they grow and plant wild celery both in and out of the classroom. After students have the plants, Ullmann and other project partners will return in the spring for additional lessons on the connections between waterfowl and history of the Back Bay area, and why wild celery, and SAV more broadly, is so important to the fish and wildlife in the area. In all, the project will involve around 600 students.

Student field trips to Back Bay are set to happen in April or May. On this excursion, 25-30 students will travel to Back Bay to plant the wild celery plants they’ve been growing in their classrooms. Using Dr. Sweeten’s technique, students will fence in wild celery that’s planted in Back Bay. To evaluate the success of this technique, students from Green Clubs at participating schools will return to Back Bay in June to measure plant growth and estimate predation issues that may have occurred since the wild celery was transplanted.

As the project unfolds from classrooms to Back Bay, interns with the Atlantic Wildfowl Heritage Museum will document the entire process for an exhibit that will be revealed during summer 2025. This exhibit will outline the work that was done over the course of the year, highlighting the benefits it will bring to the region and the importance conserving and restoring wetlands.

A Collaborative Effort

Project leaders and partners all expressed huge excitement for the project. Harrington said she was eager to return to her roots (both literally and figuratively) through this project. She volunteered previously with Grasses for the Masses, a group dedicated to planting wild celery in the Chesapeake Bay region to “bolster underwater grass populations.” She says she’s excited to “indirectly” engage in this work again and incorporate the rich history of False Cape and Back Bay into the teacher trainings and classroom lessons . Erica Ryder of BBNWR shared the same sentiment. Ryder has collaborated with Ullmann in the past on two other teacher workshops. She proclaimed, “This is the best teacher workshop that I’ve ever done. The experience that the teachers have been able to have through this workshop is really amazing.” She also elaborated how follow-up metrics will be a huge strength of this project. Project partners will be able to see how the information learned at the trainings translates to classroom results “which is not something that I was ever able to trace” previously, Ryder continued.

The SAVe Our Wetlands project will continue this fall into spring 2025 with plans to engage everyone from research scientists to educators and students. This project brings together a diverse group of partners while championing environmental stewardship and revitalizing one of the Albemarle-Pamlico region’s most valuable, yet least known aquatic ecosystems: submerged aquatic vegetation.